Children develop a number of skills inside and outside of the classroom across a continuum of complexity. Some of these skills developmentally and conceptually are relatively limited in scope. For example, in English there are only 26 letters in the alphabet and 44 phonemes. These are referred to as “constrained skills,” which can be directly taught and have a defined ceiling for mastery (Paris, 2005; Stahl, 2011; Snow and Matthews, 2016). Professor James Kim refers to word-reading skills as “fixed, finite, and teachable.” Most typically developing children can learn word-reading skills with two to three years of good systematic phonics instruction (Moats, 2020; Pearson et al 2020). Constrained skills are not limited to word-reading or literacy. Other examples include name writing, common spelling rules, counting, and basic arithmetic.

On the other end of the continuum are a set of skills that developmentally and conceptually are relatively broad in scope. These skills take a prolonged amount of time to develop, build upon themselves over time, and become more complex in adolescence and into adulthood. Examples in literacy include vocabulary, background knowledge, and comprehension. These are referred to as “unconstrained skills,” which are acquired gradually over time. To extend Professor James Kim’s description, unconstrained skills are not fixed, not finite, but they are teachable. Children’s varied experiences outside of the classroom make considerable contributions to their development of unconstrained skills. But what educators do in the classroom makes a significant impact as well.

Comprehension–extracting, constructing, and integrating meaning–is a continuum that first develops in oral language contexts and continues to develop in written language contexts (Kim, 2023). Listening comprehension is the ability to comprehend spoken language at the discourse level – including conversations, stories (i.e., narratives), and informational oral texts (Kim, 2020a). When children listen to read alouds, engage in rich discussions (extended conversations) about a topic, or understand audiobooks, they are developing their unconstrained comprehension skills through oral text.

There are two basic levels of comprehension: shallow (low-level) and deep (high-level) (Kim & Petscher, 2021; Kim, Walters & Lee, 2023). Shallow or low-level comprehension is literal understanding of text. Deep or high-level comprehension involves use of text clues and prior knowledge to derive meaning from text that often involves going beyond what is explicitly stated (e.g. inferences, reasoning, etc.). Meeting or exceeding expectations for reading comprehension on state reading assessments requires deep comprehension.

Listening comprehension is a key pathway to reading comprehension (Pearson et al, 2020). Comprehension skills are fundamentally language skills. The abilities that we associate with comprehension of written text begin with comprehension of oral text. This means that children can begin to develop deep (inferential) comprehension skills well before they are able to read independently. The primary difference between listening comprehension and reading comprehension is the presence of oral text or written text (reading comprehension) (Kim, 2023). Composed of multiple language and cognitive subcomponents, listening comprehension skills need to begin to develop before children begin Pre-K or elementary school. Once children are in formal classroom settings, literacy instruction should simultaneously develop both their constrained and unconstrained skills in order to maximize students’ opportunity for reading proficiency. Once a child can decode proficiently, they should be able to understand anything by eye that they can grasp by ear (Shanahan, 2023).

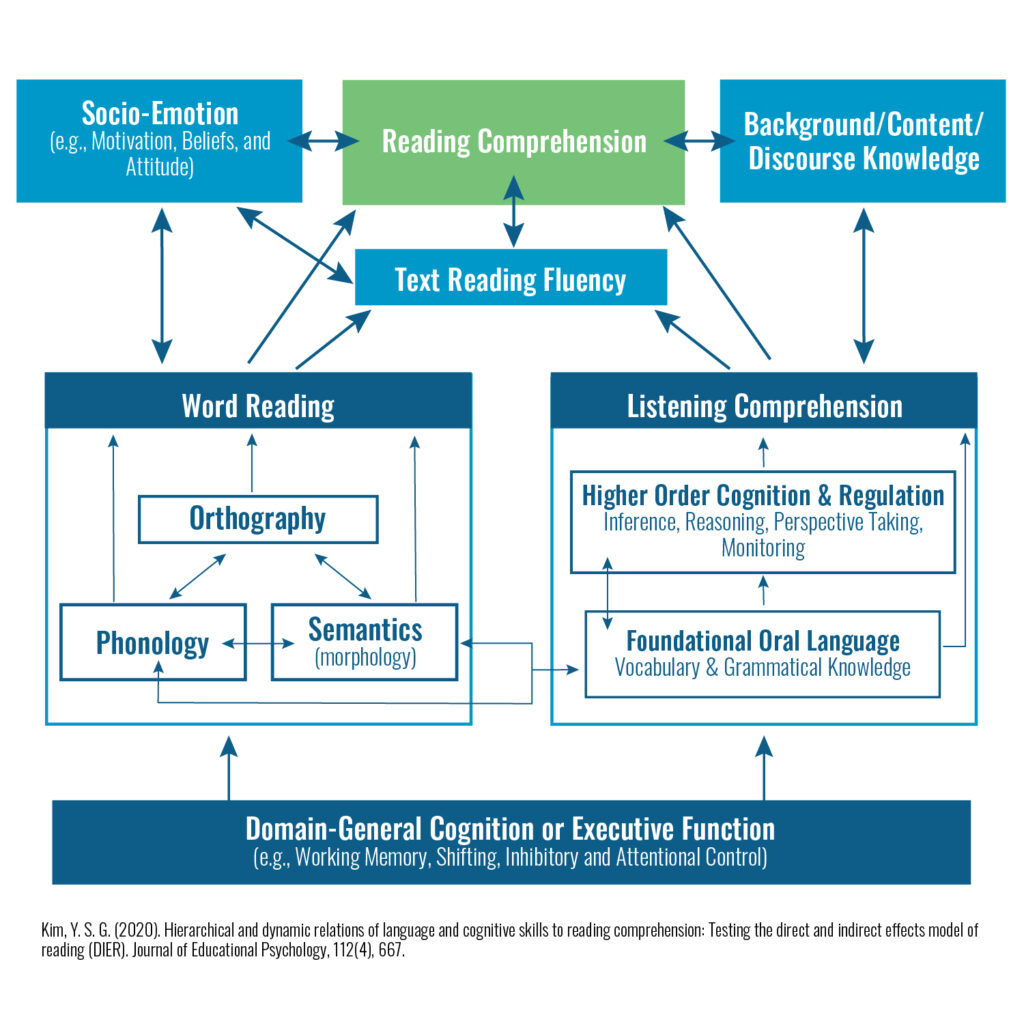

Advances in reading science over the past decade not only shine a light on the important role of language skills to reading comprehension, but also the components that make up and contribute to listening comprehension. Empirical research by two independent groups of researchers – the Language and Reading Research Consortium (LARRC) and Young-Suk Grace Kim – demonstrated listening comprehension skills are grouped into lower-level and higher-level skills (Justice and Jiang, 2023; Kim, 2020a). Lower-level skills are foundational oral language skills. Higher-level skills are meaning-construction skills. These subgroups of skills work together to impact children’s ability to make meaning from oral text (listening comprehension).

Both research groups identify vocabulary and grammar/syntax as key lower-level skills. The researchers, however, slightly split on identification of higher-level skills. Both groups of researchers include inferencing and comprehension monitoring among higher-level listening comprehension skills. LARRC also adds text structure knowledge as a key higher-level skill. Young-Suk Grace Kim adds reasoning and perspective taking as high-level skills, and places text structure knowledge outside of listening comprehension within background knowledge. We combine findings from both groups of researchers and include all five as higher-level listening comprehension skills.

Part of the appeal of well-established models of reading such as the Simple View of Reading (1986), Five Pillars of Reading (2000), and Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001) is their simplicity. They are easy to understand and research over the years has validated the importance of their components. However, advances in reading science over the past two decades have deepened our understanding of how reading works, adding additional layers of complexity to these well-known models (Duke & Cartwright, 2020; Kim, 2020a).

The language, cognitive, and reading skills that contribute to reading comprehension are connected in a chain of relations (Kim, 2023). For example, phonemic awareness and letter-sound correspondence support decoding, which supports word reading fluency, which supports text reading fluency, which supports reading comprehension. Lower-level language skills (e.g. vocabulary and grammar) support higher-level language skills (inferencing, perspective taking, etc.), which supports listening comprehension, which supports text reading fluency and reading comprehension. In this ranked chain of relations, the three most direct predictors of reading comprehension are word reading, text reading fluency, and listening comprehension.

In the earliest phases of reading development, supported by its lower level skills, word reading has a direct and significant impact on reading comprehension.

But as automaticity increases, this relationship shifts and the impact of word reading skills on reading comprehension occurs entirely through text reading fluency (Kim & Wagner, 2015). In the earliest phases of reading, listening comprehension does not have a direct relationship with text reading fluency because of the constraining influence of word reading skills (Kim, 2015; Kim, 2023).

But as word reading becomes more automatic, listening comprehension skills begin to contribute to text reading fluency. However, unlike word reading skills, listening comprehension always maintains a direct relationship and influence on reading comprehension ability. This helps explain why measures of text reading fluency do not fully capture reading comprehension – listening comprehension and background knowledge make distinct and separate contributions (Kim, 2023).

Language, cognitive, and reading skills interact with each other to shape reading comprehension. For example, background knowledge, vocabulary, and grammar influence listening comprehension and reading comprehension. As a result, individual skills have both direct and indirect effects on both listening comprehension and reading comprehension (Kim, 2020b; Kim, 2023). For example, vocabulary in second grade has a large impact on listening comprehension. About half of the impact is direct, meaning that a greater vocabulary knowledge directly contributes to high-level comprehension of oral text (e.g. conversations, read alouds, etc.). Vocabulary also supports the functioning of other important subskills – this is its indirect effect. A student who knows many words (vocabulary) is better equipped to fill in gaps while reading (inferences), evaluate a character’s point of view and motivations (perspective taking), and comprehend complex sentences (grammar/syntax).

An important high-level interaction exists between word reading and listening comprehension from the earliest phases of reading development (Language and Reading Research Consortium, 2015; Kim & Wagner, 2015). Improvement in one set of skills benefits the other set of skills. A longitudinal study in Norway finds that early language comprehension at age 4 is strongly related to code-related skills (phoneme awareness, letter knowledge, and rapid naming), and indirectly influences decoding through these subskills (Hjetland, et al, 2019). Researchers find the key point of interaction between word reading and listening comprehension is between morphological awareness (understanding of the parts of words – morphemes – and how they work together) and vocabulary anchored by executive function skills (Kim, 2020b; Kim 2023b). The interactive nature of the skills have key implications for instruction: students need both word reading and listening comprehension instruction and instruction should happen simultaneously across skills, as development in one skill can positively impact other skills.

The contributions of individual skills to listening comprehension and reading comprehension are not static. They change in relation to each other at different phases of reading development. In the early years of reading development, word reading has the greatest influence on reading comprehension (Kim & Wagner, 2015; Language and Reading Research Consortium, 2015). It also has a constraining role; its level of influence is so great that it limits the contributions of other skills. But as word reading develops, its constraining role on other reading skills decreases. Listening comprehension and associated skills begin to play greater roles on reading comprehension ability (Kim, 2023; Justice & Jiang, 2023). For example, in second grade the contribution of vocabulary to reading comprehension is about one-third the size of the impact of word reading skills. But by fourth grade, vocabulary’s contribution to reading comprehension is on par with that of word reading skills. Perspective taking makes a similar leap in relative importance to reading comprehension between second and fourth grades im, 2020b).

Although improvement in word reading skills makes strong contributions to reading comprehension in the early phases of reading, listening comprehension and other associated skills (e.g. executive function, background knowledge) begin to play even greater roles as word reading skills develop. These unconstrained skills take more time to develop. Although their impact may be less visible in the early phases of reading development, they play a significant role in children’s advancement and therefore need early and implicit instruction in tandem with word reading instruction.

It’s important to keep in mind that these research findings represent overall patterns of grade-level reading development over time. At the classroom level, teachers needs to use assessment data to guide instruction for individual students (Snow, Burns & Griffin, 1998; Pearson et al, 2020; Duke & Cartwright, 2021; Kim, 2020a). For example, there is evidence that the shift to reliance on language-based skills occurs later for struggling multilingual learners, which highlights the need for early screening and support for lower- and higher-level listening comprehension skills (Mancilla-Martinez & Lesaux, 2017; Mancilla-Martinez, 2023).

A newer model of reading that educators might be familiar with is the Active View of Reading. This research-based model of reading makes advances on earlier models, such as the Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Reading Rope, by explicitly focusing on “contributors to reading—and, thus, potential causes of reading difficulty—within, across, and beyond the broad categories of word recognition and language comprehension” (Duke and Cartwright, 2021). It illustrates the importance of both word reading and language skills to reading comprehension, but also explicitly incorporates “bridging processes” between the two. The Active View of Reading seeks to provide practical guidance for educators and illuminate multiple factors that contribute to reading comprehension challenges.

A key strength of the Active View of Reading is how it provides a clear picture for educators of targets for instruction to assist children struggling with reading comprehension.

The model incorporates other aspects beyond word reading and listening comprehension, such as motivation, strategy use, and executive function skills. As the authors note, although the model is supported by research, it has not yet been tested as a whole to analyze how the parts work together or change over time. Nonetheless, educators likely will find the Active View of Reading helpful as they seek to make instructional decisions in the classroom for children struggling with reading comprehension.

Comprehension is the process of extracting, constructing, and integrating meaning. Readers use their prior knowledge to make meaning of text, anticipate forthcoming information as they consume text, and update their prior knowledge with new information as they interpret new text. This means that knowledge is key to both listening comprehension and reading comprehension (Cabell & Hwang, 2020). Depending upon their perspective, researchers use different terms and emphasize various types of knowledge involved in student reading and learning: background, domain, content, discourse, world, declarative, procedural, conditional, cultural, epistemic, linguistic, principled, and strategic (Pearson et al, 2020; Kim, 2023; Cabell and Hwang, 2020; Duke & Cartwright, 2021; Hattan and Lupo, 2020).

Knowledge is not prominent in popular depictions of the Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, 1986; Hoover & Gough, 1990), though its proponents do acknowledge its connection with comprehension (Gough, Hoover & Peterson, 1996). In the Direct and Inferential Model of Reading (DIME), background knowledge and vocabulary represent the linguistic comprehension part of the Simple View of Reading (Ahmed et al, 2016). Knowledge is not prominently addressed in the National Reading Panel report (National Reading Panel, 2000), nor is it included among the “five pillars of reading.” Knowledge is explicitly included in Scarborough’s Reading Rope, with distinctions made between background knowledge (facts, concepts, etc.) and literacy knowledge (print concepts, genre, etc.). Scarborough situates both types of knowledge within the language comprehension strand, along with vocabulary, language structure, and verbal reasoning (Scarborough, 2001). Similarly, the Active View of Reading places reading-specific background knowledge (genre, text features, etc.) and cultural and other content knowledge within language comprehension (Duke & Cartwright, 2021). By contrast, the Direct and Indirect Effects Model of Reading (DIER) situates knowledge (content/topic, world, and discourse) outside of listening comprehension, with direct interactions between listening comprehension and reading comprehension separately (Kim, 2020a; Kim, 2023).

Multiple studies show knowledge makes contributions to reading comprehension beyond word reading and listening comprehension (Duke & Cartwright, 2021). Although there is a reciprocal relationship between knowledge and vocabulary (Hwang & Cabell, 2021), empirical studies suggest knowledge makes contributions beyond vocabulary knowledge (Pearson et al, 2020). Students with lower levels of general comprehension but higher background knowledge have been shown to outperform students with higher levels of comprehension but lower background knowledge. One of the most famous examples of this is the baseball experiment in which students with lower reading levels but greater familiarity with baseball had higher results on a verbal retell task than students with higher reading levels but lower familiarity with the rules of the game (Recht & Leslie, 1988). Researchers have also found that greater background knowledge appears to assist reading comprehension of text with lower levels of cohesion (logical and meaningful flow of text structure) (Pearson et al, 2020). In fact, researchers find that background knowledge plays an increasing role for comprehension as students move through middle and high school (Ahmed, 2016).

Listening comprehension has a complexity and nuance that parallels that of word-reading skills.

Phonemic awareness

Letter knowledge

Letter-sound correspondence

Morphology (parts of words)

Decoding

Word reading accuracy

Word reading fluency

Vocabulary

Grammar & Syntax

Inferencing

Reasoning

Perspective Taking

Comprehension Monitoring

Text Structure Awareness

Assessment and instruction of listening comprehension requires clear understanding of these component skills. This section provides expanded definitions to assist educators and practitioners.

Vocabulary is the knowledge of words and their meanings. Word knowledge comes in two forms – receptive and productive. Receptive vocabulary includes words that we recognize when we hear them. Productive (expressive) vocabulary includes words that we use when we speak. Receptive vocabulary is typically larger than productive vocabulary, and may include words to which we assign some meaning, even if we do not know their explicit definitions and connotations – or use them ourselves as we speak. Another dimension of vocabulary is “depth”-- students’ ability to make associations between the meanings of words (semantic connections) among related domain vocabulary (Kim et al, 2021).

Inference is information not expressed explicitly by oral or written text but derived by the listener or reader on the basis of their knowledge (Ababneh & Ramadan, 2013). It is encoded in a mental representation of the text. Inferencing is a central component of oral and written discourse understanding and involves the derivation of new information and/or the activation of available (prior) knowledge. In oral text, inferences can be used to identify an unclearly pronounced word, to settle on the meaning of a word, to determine the referent of a pronoun, or to determine an intended message from a literal meaning. Inference generation is the process by which a reader integrates information within or across (oral or written) texts to create new understandings (Hall et al, 2020). Researchers describe two types of inferences: text-connecting inferences and gap-filling inferences. Text-connecting inferences rely on linguistic cues (e.g. inference of word meanings from context clues) present in the text. Gap-filling inferences (also called knowledge-based inferences) compel the reader to go beyond the text and draw on background knowledge. This connection with knowledge is one of the reciprocal pathways between listening comprehension and background knowledge.

Comprehension monitoring is the ability to reflect on and evaluate one’s comprehension of spoken or written text (Kim & Phillips, 2016; Justice & Jiang, 2023). It is typically evaluated by assessing children’s ability to detect inconsistencies in stories. In addition to ongoing self-assessment of one’s own comprehension of a text, comprehension monitoring also involves application of corrective strategies (or “repair”) when comprehension is suffering. Researchers find that comprehension monitoring skills predict listening comprehension skills in kindergarten and first grade, and when considered as part of the larger array of listening comprehension skills predict reading comprehension in third grade (Justice & Jiang, 2023). Researchers find that students’ comprehension monitoring skills in first grade have an impact on their reading comprehension in third grade, even after taking into account their vocabulary, decoding skills, and working memory. Comprehension monitoring has an impact on reading comprehension across grade levels. Researchers find comprehension monitoring distinguishes adequate comprehenders from poor comprehenders in middle and high school (Pearson et al, 2020.)

Verbal reasoning is the ability to use language to solve and analyze problems (Tighe, Spencer & Schatschneider, 2015). It is sometimes described as the ability to “think with words.” Reasoning, however, is more than vocabulary knowledge or oral language skills. It is a broad analytical and problem-solving concept that includes both deduction (bottom-up from specific to general) and induction (top-down from general to specific). When children ask “who-what-why” questions, they are using reasoning skills, which are an essential part of learning to use their language skills to identify, understand, and solve problems. Children use reasoning skills when they make inferences or interpret nonliteral meanings of metaphors and figures of speech (Duke & Cartwright, 2021). Reasoning is involved when children have to understand letter sequences or identify which word doesn’t belong in a group of words. Reasoning is a learned skill that helps children follow directions, develop solutions to problems, and draw conclusions with incomplete or imperfect information. Inference and perspective taking can be considered specific types of reasoning skills. Students use different types of reasoning skills in understanding oral and written texts (including visuospatial reasoning to construct accurate mental representations of texts with graphs or visual presentations).

Text structure refers to how text is organized to convey meaning to the reader (Shanahan et al, 2010). It applies to both narrative and informational text. Text structure awareness is a familiarity and understanding of how ideas, sentences, paragraphs, and passages of text are typically organized in oral and written contexts. It assists students in the process of comprehension – extracting, constructing, and integrating meaning.

For narrative text, text structure awareness involves the explicit understanding of how stories are organized–the characters, setting, goal, problem, plot, and resolution (Shanahan et al, 2010). These structural elements give the story meaning and “shape.” Awareness of the structure of narrative texts helps children mentally visualize story elements and anticipate what might happen later in the story. Text structure awareness helps students to analyze and comprehend the main ideas, themes, and lessons from a narrative text. Many narrative texts follow a simple structure – a series of related events. This makes awareness of narrative text structure easier to acquire for most typically developing readers (Best, Floyd & McNamara, 2008).

For informational text – also referred to as “expository text” – text structure awareness involves an understanding of the structures that organize ideas in a text, such as cause and effect, compare and contrast, problem and solution, and sequence, and the vocabulary used to convey meaning to the reader. Expository text structure typically involves paragraphs and passages; the text as a whole may include multiple layers of different structures (Shanahan et al, 2010). There are common clue words associated with different expository text structures. For example, sequences of ideas in a text are often signaled to the reader using words like first, next, then, after, and finally. In contrast with narrative text, informational text generally has more complex structures. This increases the processing demands on the reader, who has to contend with greater structural complexity, greater information density, and greater knowledge demands (Best, Floyd & McNamara, 2008).

An awareness of common expository text structures, and associated signal words, can aid students’ comprehension monitoring. This can be particularly helpful with less cohesive text, where the logical and meaningful flow of text is less explicit (Pearson et al, 2020). There are some important differences in text structures found in written text compared to oral text. For example, written text includes punctuation and graphical elements of text (e.g. pictures, diagrams, etc.) that do not exist in oral text. Written text also offers different opportunities to engage with text structure, such as previewing text and use of graphic organizers (Duke, Ward & Pearson, 2021). This suggests important differences and opportunities in instruction of text structures between oral text and written text.

Ababneh, T., & Ramadan, S. (2013). Inferences in the Comprehension of Language. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(4), 48-51.

Ahmed, Y., Francis, D. J., York, M., Fletcher, J. M., Barnes, M. A., & Kulesz, P. (2016). Validation of the direct and mediation (DIME) model of reading comprehension in grades 7 through 12. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 44, 68–82.

Best, R. M., Floyd, R. G., & McNamara, D. S. (2008). Differential competencies contributing to children’s comprehension of narrative and expository texts. Reading Psychology, 29, 137–164.

Cabell, S. Q., & Hwang, H. (2020). Building content knowledge to boost comprehension in the primary grades. Reading Research Quarterly, 55, S99-S107.

Cervetti, G. N., et al. (2020). How the reading for understanding initiative’s research complicates the simple view of reading invoked in the science of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 55, S161-S172. Available online here.

Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56, S25-S44. Available online here.

Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and special education, 7(1), 6-10.

Gough, P. B., Hoover, W. A., & Peterson, C. L. (2013). Some observations on a simple view of reading. In Reading Comprehension Difficulties (pp. 1-13). Routledge.

Hall, C., Vaughn, S., Barnes, M. A., Stewart, A. A., Austin, C. R., & Roberts, G. (2020). The effects of inference instruction on the reading comprehension of English learners with reading comprehension difficulties. Remedial and Special Education, 41(5), 259-270.

Hattan, C., & Lupo, S. M. (2020). Rethinking the role of knowledge in the literacy classroom. Reading Research Quarterly, 55, S283-S298.

Hjetland, H. N., Lervåg, A., Lyster, S. A. H., Hagtvet, B. E., Hulme, C., & Melby-Lervåg, M. (2019). Pathways to reading comprehension: A longitudinal study from 4 to 9 years of age. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(5), 751.

Hoover, W. A., & Gough, P. B. (1990). The simple view of reading. Reading and writing, 2, 127-160.

Hu, T. C., Sung, Y. T., Liang, H. H., Chang, T. J., & Chou, Y. T. (2022). Relative roles of grammar knowledge and vocabulary in the reading comprehension of EFL elementary-school learners: Direct, mediating, and form/meaning-distinct effects. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 827007.

Hwang, H., and Cabell, S. Q. (2021) Latent profiles of vocabulary and domain knowledge and their relation to listening comprehension in kindergarten. Journal of Research in Reading, 44: 636–653.

Justice, L. M., & Jiang, H. (2023). Language is the basis of skilled reading comprehension. Handbook on the Science of Early Literacy, 131.

Kim, J. S., Burkhauser, M. A., Mesite, L. M., Asher, C. A., Relyea, J. E., Fitzgerald, J., & Elmore, J. (2021). Improving reading comprehension, science domain knowledge, and reading engagement through a first-grade content literacy intervention. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(1), 3.

Kim, Y. S. G. (2015). Developmental, component‐based model of reading fluency: An investigation of predictors of word‐reading fluency, text‐reading fluency, and reading comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 50(4), 459-481. Available online here.

Kim, Y.S. (2020a). Simple but not simplistic: The simple view of reading unpacked and expanded. The Reading League, May/June, 15-22. Available online here.

Kim, Y.S. (2020b). Hierarchical and dynamic relations of language and cognitive skills to reading comprehension: Testing the direct and indirect effects model of reading (DIER). Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(4): 667-684.

Kim, Y. S. G. (2020c). Theory of mind mediates the relations of language and domain-general cognitions to discourse comprehension. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 194, 104813.

Kim, Y. S. G. (2023). Simplicity Meets Complexity. Handbook on the Science of Early Literacy, 9-22. Available online here.

Kim, Y. S. G. (2023b). Executive Functions and Morphological Awareness Explain the Shared Variance between Word Reading and Listening Comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 27(5), 451–474.

Kim, Y.S. & Snow, C. (2021). The science of reading is incomplete without the science of teaching reading. The Reading League, September/October, 5-13. Available online here.

Kim, Y. S. G., & Wagner, R. K. (2015). Text (oral) reading fluency as a construct in reading development: An investigation of its mediating role for children from grades 1 to 4. Scientific Studies of Reading, 19(3), 224-242.

Kim, Y. G., & Petscher, Y. (2021). Influences of individual, text, and assessment factors on text/discourse comprehension in oral language (listening comprehension). Annals of Dyslexia, 71(2), 218–237.

Kim, Y. S. G., & Phillips, B. (2016). Five minutes a day to improve comprehension monitoring in oral language contexts: An exploratory intervention study with prekindergartners from low-income families. Topics in Language Disorders, 36(4), 356-367.

Kim, Y. S. G., Dore, R., Cho, M., Golinkoff, R., & Amendum, S. J. (2021). Theory of mind, mental state talk, and discourse comprehension: Theory of mind process is more important for narrative comprehension than for informational text comprehension. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 209, 105181.

Kim, Y.S. G., Wolters, A., & Lee, J.W. (2024). Reading and writing relations are not uniform: They differ by the linguistic grain size, developmental phase, and measurement. Review of Educational Research, 94(3), 311-342.

Language and Reading Research Consortium. (2015). Learning to read: Should we keep things simple?. Reading Research Quarterly, 50(2), 151-169.

Mancilla-Martinez, J. (2023). Prioritizing Dual Language Learners’ Language Comprehension Development to Support Later Reading Achievement. Handbook on the Science of Early Literacy, 32.

Mancilla-Martinez, J., & Lesaux, N. K. (2017). Early indicators of later English reading comprehension outcomes among children from Spanish-speaking homes. Scientific Studies of Reading, 21(5), 428-448.

Moats, L.C. (1999). Teaching reading “is” rocket science: What expert teachers of reading should know and be able to do. Washington, DC: American Federation of Teachers Available online here.

Moats, L. C. (2020). Teaching reading “is” rocket science: What expert teachers of reading should know and be able to do. American Educator, 44(2), 4. Available online here.

National Reading Panel (US), National Institute of Child Health, & Human Development (US). (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Paris, S. G. (2005). Reinterpreting the development of reading skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 40(2), 184-202.

Pearson, P. D., Palincsar, A. S., Biancarosa, G., & Berman, A. I. (Eds.). (2020). Reaping the Rewards of the Reading for Understanding Initiative. Washington, DC: National Academy of Education. Available online here.

Recht, D. R., & Leslie, L. (1988). Effect of prior knowledge on good and poor readers' memory of text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(1), 16.

Scarborough, H. S., (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. Approaching difficulties in literacy development: Assessment, pedagogy and programmes, 10, 23-38. Available online here.

Shanahan, Tim. (2023, June 17). What is linguistic comprehension in the simple view of reading? Shanahan On Literacy. Available online here.

Shanahan, T., Callison, K., Carriere, C., Duke, N. K., Pearson, P. D., Schatschneider, C., & Torgesen, J. (2010). Improving reading comprehension in kindergarten through 3rd grade: A practice guide (NCEE 2010-4038). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (Eds.). (1998). Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

Snow, C. E., & Matthews, T. J. (2016). Reading and language in the early grades. The Future of Children, 26, 57–74

Stahl, K.A.D. (2011). Applying new visions of reading development in today's classrooms. The Reading Teacher, 65(1), 52-56.

Tighe, E. L., Spencer, M., & Schatschneider, C. (2015). Investigating predictors of listening comprehension in third-, seventh-, and tenth-grade students: a dominance analysis approach. Reading Psychology, 36(8), 700-740.

Search the directory for instructional resources such as activities, strategies, practices, student platforms, supplemental curricula, and interventions as well as assessments to target listening comprehension in the classroom.

Sign up and we’ll update you as we add new resources to support your classroom listening comprehension instruction.

Read Charlotte is a community initiative that unites educators, community partners, and families to improve children’s reading from birth to third grade. We don’t run programs. We are a capacity-building intermediary that supports local partners to apply evidence-based knowledge about effective reading instruction and interventions, high-quality execution, continuous improvement, and data analysis to improve reading outcomes.

Read Charlotte is a civic initiative of Foundation For The Carolinas.

Reference in this website to any specific commercial products, processes, or services, or the use of any trade, firm, or corporation name is for the information and convenience of the public and does not constitute endorsement or recommendation by Read Charlotte or the Foundation For The Carolinas. Our office is not responsible for and does not in any way guarantee the accuracy of information in other sites accessible through links herein. Read Charlotte and/or the Foundation For The Carolinas may supplement this list with other services and products that meet the specified criteria. For more information contact: charlotte@readcharlotte.org.